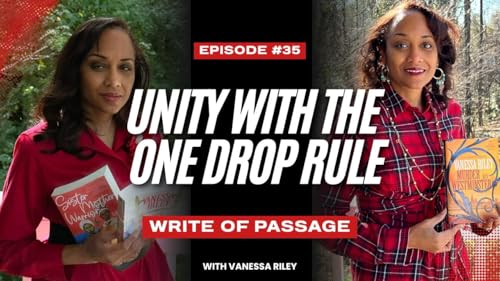

Unity with the One Drop Rule

Échec de l'ajout au panier.

Veuillez réessayer plus tard

Échec de l'ajout à la liste d'envies.

Veuillez réessayer plus tard

Échec de la suppression de la liste d’envies.

Veuillez réessayer plus tard

Échec du suivi du balado

Ne plus suivre le balado a échoué

-

Narrateur(s):

-

Auteur(s):

À propos de cet audio

Pas encore de commentaire